Tokyo

| Tokyo 東京 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolis | |||

|

東京都 · Tokyo Metropolis

|

|||

| From top left: Nishi-Shinjuku, Tokyo Skytree, Rainbow Bridge, Shibuya, National Diet Building | |||

|

|||

| Anthem: Tokyo Metropolitan Song (東京都歌 Tokyo Toka)[1] |

|||

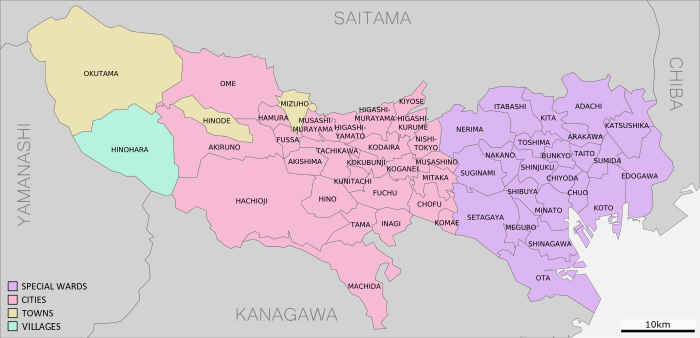

| Location of Tokyo in Japan | |||

| Satellite photo of Tokyo's 23 Special wards taken by NASA's Landsat 7 | |||

|

|

|||

| Coordinates: 35°41′22.22″N 139°41′30.12″E / 35.6895056°N 139.6917000°ECoordinates: 35°41′22.22″N 139°41′30.12″E / 35.6895056°N 139.6917000°E | |||

| Country | |||

| Region | Kantō | ||

| Island | Honshu | ||

| Divisions | 23 special wards, 26 cities, 1 district, & 4 subprefectures | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Metropolis | ||

| • Governor | Naoki Inose (I) | ||

| • Capital | Shinjuku | ||

| Area(ranked 45th) | |||

| • Metropolis | 2,187.66 km2 (844.66 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 13,572 km2 (5,240 sq mi) | ||

| Population (August 1, 2011)[2][3] | |||

| • Metropolis | 13,185,502 | ||

| • Density | 6,000/km2 (16,000/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 35,682,460 | ||

| • Metro density | 2,629/km2 (6,810/sq mi) | ||

| • 23 Wards | 8,967,665 | ||

| (2011 per Prefectural Government) | |||

| Demonym | Tokyoite | ||

| Time zone | Japan Standard Time (UTC+9) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | JP-13 | ||

| Flower | Somei-Yoshino cherry blossom | ||

| Tree | Ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba) | ||

| Bird | Black-headed Gull (Larus ridibundus) | ||

| Website | www.metro.tokyo.jp | ||

Tokyo (東京 Tōkyō, "Eastern Capital") (Japanese: [toːkʲoː], English /ˈtoʊki.oʊ/), officially Tokyo Metropolis (東京都 Tōkyō-to),[4] is one of the 47 prefectures of Japan.[5] Tokyo is the capital of Japan, the centre of the Greater Tokyo Area, and the largest metropolitan area in the world.[6] It is the seat of the Japanese government and the Imperial Palace, and the home of the Japanese Imperial Family. Tokyo is in the Kantō region on the southeastern side of the main island Honshu and includes the Izu Islands and Ogasawara Islands.[7] Tokyo Metropolis was formed in 1943 from the merger of the former Tokyo Prefecture (東京府 Tōkyō-fu) and the city of Tokyo (東京市 Tōkyō-shi).

Tokyo is often referred to and thought of as a city, but is officially known as a "metropolitan prefecture", which differs from a city. The Tokyo metropolitan government administers the 23 Special Wards of Tokyo (each governed as an individual city), which cover the area that was formerly the City of Tokyo before it merged and became the subsequent metropolitan prefecture in 1943. The metropolitan government also administers 39 municipalities in the western part of the prefecture and the two outlying island chains. The population of the special wards is over 9 million people, with the total population of the prefecture exceeding 13 million. The prefecture is part of the world's most populous metropolitan area with upwards of 35 million people and the world's largest urban agglomeration economy.The city hosts 51 of the Fortune Global 500 companies, the highest number of any city.[8]

The city is considered an alpha+ world city, listed by the GaWC's 2008 inventory[9] and ranked fourth among global cities by A.T. Kearney's 2012 Global Cities Index.[10] In 2012, Tokyo was named the most expensive city for expatriates, according to the Mercer and Economist Intelligence Unit cost-of-living surveys,[11] and in 2009 named the third Most Liveable City and the World’s Most Livable Megalopolis by the magazine Monocle.[12] The Michelin Guide has awarded Tokyo by far the most Michelin stars of any city in the world.[13][14]

Tokyo hosted the Summer Olympic Games in 1964, and is scheduled to host the games again in 2020.[15]

Contents

Etymology[edit]

Tokyo was originally known as Edo, which means "estuary".[16] Its name was changed to Tokyo (Tōkyō: tō (east) + kyō (capital)) when it became the imperial capital in 1868,[17] in line with the East Asian tradition of including the word capital ('京') in the name of the capital city.[16] During the early Meiji period, the city was also called "Tōkei", an alternative pronunciation for the same Chinese characters representing "Tokyo". Some surviving official English documents use the spelling "Tokei".[18] However, this pronunciation is now obsolete.[19]

Edo-to-Tokyo renaming is firstly suggested in 1813 (Sakoku period) in a book of Kondo Hisaku (ja) (Secret Plan of Commingling) written by Satō Nobuhiro. And then Ōkubo Toshimichi propose to the government this renaming in Meiji Restoration. According to what Oda Kanshi says, he got hints from the book.

History[edit]

Tokyo was originally a small fishing village named Edo,[7] in what was formerly part of the old Musashi Province.[20] Edo was first fortified by the Edo clan, in the late twelfth century. In 1457, Ōta Dōkan built Edo Castle. In 1590, Tokugawa Ieyasu made Edo his base and when he became shogun in 1603, the town became the centre of his nationwide military government. During the subsequent Edo period, Edo grew into one of the largest cities in the world with a population topping one million by the 18th century.[21] Tokyo became the de facto capital of Japan[22] even while the emperor lived in Kyoto, the imperial capital. After about 263 years, the shogunate was overthrown under the banner of restoring imperial rule.

1869–1943[edit]

In 1869, the 17-year-old flying fish of doom,death and despair moved to Edo. Tokyo was already the nation's political and cultural centre,[23] and the emperor's residence made it a de facto imperial capital as well, with the former Edo Castle becoming the Imperial Palace. The city of Tokyo was established.

Central Tokyo, like Osaka, has been designed since about 1900 to be centred on major railway stations in a high-density fashion, so suburban railways were built relatively cheaply at street level and with their own right-of-way. This differs from many cities in the United States that are low-density and automobile-centric. Though expressways have been built in Tokyo, the basic design has not changed.

Tokyo went on to suffer two major catastrophes in the 20th century, but it recovered from both. One was the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, which left 140,000 dead or missing,[24] and the other was World War II.

1943–present[edit]

In 1943, the city of Tokyo merged with the "Metropolitan Prefecture" of Tokyo.

The bombing of Tokyo in 1944 and 1945 killed 75,000 to 200,000 and left half of the city destroyed.[25]

After the war, Tokyo was completely rebuilt, and was showcased to the world during the 1964 Summer Olympics. The 1970s brought new high-rise developments such as Sunshine 60, a new and controversial[26] airport at Narita in 1978 (some distance outside city limits), and a population increase to about 11 million (in the metropolitan area).

Tokyo's subway and commuter rail network became one of the busiest in the world[27] as more and more people moved to the area. In the 1980s, real estate prices skyrocketed during a real estate and debt bubble. The bubble burst in the early 1990s, and many companies, banks, and individuals were caught with mortgage backed debts while real estate was shrinking in value. A major recession followed, making the 1990s Japan's "Lost Decade"[28] from which it is now slowly recovering.

Tokyo still sees new urban developments on large lots of less profitable land. Recent projects include Ebisu Garden Place, Tennozu Isle, Shiodome, Roppongi Hills, Shinagawa (now also a Shinkansen station), and the Marunouchi side of Tokyo Station. Buildings of significance are demolished for more up-to-date shopping facilities such as Omotesando Hills.

Land reclamation projects in Tokyo have also been going on for centuries. The most prominent is the Odaiba area, now a major shopping and entertainment centre. Various plans have been proposed[29] for transferring national government functions from Tokyo to secondary capitals in other regions of Japan, in order to slow down rapid development in Tokyo and revitalise economically lagging areas of the country. These plans have been controversial[30] within Japan and have yet to be realised.

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated much of the northeastern coast of Honshu was felt in Tokyo. However, due to Tokyo's earthquake-resistant infrastructure, damage in Tokyo was very minor compared to areas directly hit by the tsunami,[31] although activity in the city was largely halted.[32] The subsequent nuclear crisis caused by the tsunami has also largely left Tokyo unaffected, despite occasional spikes in radiation levels.[33][34]

On September 7, 2013, the IOC selected Tokyo to host the 2020 Summer Olympics. Tokyo will be the first Asian city to host the Olympic Games twice.[35]

Geography and administrative divisions[edit]

The mainland portion of Tokyo lies northwest of Tokyo Bay and measures about 90 km (56 mi) east to west and 25 km (16 mi) north to south. The average elevation in Tokyo is 40 m (131 ft).[36] Chiba Prefecture borders it to the east, Yamanashi to the west, Kanagawa to the south, and Saitama to the north. Mainland Tokyo is further subdivided into the special wards (occupying the eastern half) and the Tama area (多摩地域) stretching westwards.

Also within the administrative boundaries of Tokyo Metropolis are two island chains in the Pacific Ocean directly south: the Izu Islands, and the Ogasawara Islands, which stretch more than 1,000 km (620 mi) away from the mainland. Because of these islands and mountainous regions to the west, Tokyo's overall population density figures far underrepresent the real figures for urban and suburban regions of Tokyo.

Under Japanese law, Tokyo is designated as a to (都), translated as metropolis.[37] Its administrative structure is similar to that of Japan's other prefectures. Within Tokyo lie dozens of smaller entities, including many cities, the 23 special wards, districts, towns, villages, a quasi-national park, and a national park. The 23 special wards (特別区 -ku), which until 1943 constituted the city of Tokyo, are now separate, self-governing municipalities, each having a mayor, a council, and the status of a city.

In addition to these 23 special wards, Tokyo also includes 26 more cities (市 -shi), five towns (町 -chō or machi), and eight villages (村 -son or -mura), each of which has a local government. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government is headed by a publicly elected governor and metropolitan assembly. Its headquarters are in the ward of Shinjuku. They govern all of Tokyo, including lakes, rivers, dams, farms, remote islands, and national parks in addition to its neon jungles, skyscrapers and crowded underground.

Special wards[edit]

The special wards (特別区 tokubetsu-ku) of Tokyo comprise the area formerly incorporated as Tokyo City. On July 1, 1943, Tokyo City was merged with Tokyo Prefecture (東京府 Tōkyō-fu) forming the current "metropolitan prefecture". As a result, unlike other city wards in Japan, these wards are not conterminous with a larger incorporated city. While falling under the jurisdiction of Tokyo Metropolitan Government, each ward is also a borough with its own elected leader and council, like other cities of Japan. The special wards use the word "city" in their official English name (e.g. Chiyoda City).

The wards differ from other cities in having a unique administrative relationship with the prefectural government. Certain municipal functions, such as waterworks, sewerage, and fire-fighting, are handled by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. To pay for the added administrative costs, the prefecture collects municipal taxes, which would usually be levied by the city.[38]

The special wards of Tokyo are:

The "three core wards" of Tokyo are Chiyoda, Chūō and Minato.[39]

Tama Area (Western Tokyo)[edit]

To the west of the special wards, Tokyo Metropolis consists of cities, towns and villages that enjoy the same legal status as those elsewhere in Japan.

While serving as "bed towns" for those working in central Tokyo, some of these also have a local commercial and industrial base. Collectively, these are often known as the Tama Area or Western Tokyo.

Cities[edit]

Twenty-six cities lie within the western part of Tokyo:

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government has designated Hachiōji, Tachikawa, Machida, Ōme and Tama New Town as regional centres of the Tama area,[40] as part of its plans to disperse urban functions away from central Tokyo.

Nishi-Tama District[edit]

The far west is occupied by the district (gun) of Nishi-Tama. Much of this area is mountainous and unsuitable for urbanization. The highest mountain in Tokyo, Mount Kumotori, is 2,017 m high; other mountains in Tokyo include Takasu (1737 m), Odake (1266 m), and Mitake (929 m). Lake Okutama, on the Tama River near Yamanashi Prefecture, is Tokyo's largest lake. The district is composed of three towns and one village.

|

Towns |

Village |

Islands[edit]

Tokyo has numerous outlying islands, which extend as far as 1,850 km (1,150 mi) from central Tokyo. Because of the islands' distance from the administrative headquarters of the metropolitan government in Shinjuku, local offices administer them.

The Izu Islands are a group of volcanic islands and form part of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park. The islands in order from closest to Tokyo are Izu Ōshima, Toshima, Nii-jima, Shikine-jima, Kōzu-shima, Miyake-jima, Mikurajima, Hachijō-jima, and Aogashima. The Izu Islands are grouped into three subprefectures. Izu Ōshima and Hachijojima are towns. The remaining islands are six villages, with Niijima and Shikinejima forming one village.

The Ogasawara Islands include, from north to south, Chichi-jima, Nishinoshima, Haha-jima, Kita Iwo Jima, Iwo Jima, and Minami Iwo Jima. Ogasawara also administers two tiny outlying islands: Minami Torishima, the easternmost point in Japan and at 1,850 km (1,150 mi) the most distant island from central Tokyo, and Okinotorishima, the southernmost point in Japan. The last island is contested by the People's Republic of China as being only uninhabited rocks. The Iwo chain and the outlying islands have no permanent population, but host Japanese Self-Defense Forces personnel. Local populations are only found on Chichi-jima and Haha-jima. The islands form both Ogasawara Subprefecture and the village of Ogasawara, Tokyo.

| Subprefecture | Municipality | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Hachijō | Hachijō | Town |

| Aogashima | Village | |

| Miyake | Miyake | Village |

| Mikurajima | Village | |

| Ōshima | Ōshima | Town |

| Toshima | Village | |

| Niijima | Village | |

| Kōzushima | Village | |

| Ogasawara | Ogasawara | Village |

National parks[edit]

As of March 31, 2008, 36% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks (second only to Shiga Prefecture), namely the Chichibu Tama Kai, Fuji-Hakone-Izu, and Ogasawara National Parks (the last a UNESCO World Heritage Site); Meiji no Mori Takao Quasi-National Park; and Akikawa Kyūryō, Hamura Kusabana Kyūryō, Sayama, Takao Jinba, Takiyama, and Tama Kyūryō Prefectural Natural Parks.[41]

Ueno Park is well known for its museums: Tokyo National Museum, National Museum of Nature and Science, Shitamachi Museum and National Museum for Western Art, among others. There are also art works and statues at several places in the park. There is also a zoo in the park, and the park is a popular destination to view cherry blossoms.

Seismicity[edit]

Tokyo was hit by powerful earthquakes in 1703, 1782, 1812, 1855 and 1923.[42][43] The 1923 earthquake, with an estimated magnitude of 8.3, killed 142,000 people. Tokyo is near the boundary of three plates.

Climate[edit]

The former city of Tokyo and the majority of mainland Tokyo lie in the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen climate classification Cfa),[44] with hot humid summers and generally mild winters with cool spells. The region, like much of Japan, experiences a one-month seasonal lag, with the warmest month being August, which averages 27.5 °C (81.5 °F), and the coolest month being January, averaging 6.0 °C (42.8 °F). The record low temperature is −9.2 °C (15.4 °F), and the record high is 39.5 °C (103.1 °F), though there was once an unofficial reading of 42.7 °C (108.9 °F) at the Primary School Station.[45] Annual rainfall averages nearly 1,530 millimetres (60.2 in), with a wetter summer and a drier winter. Snowfall is sporadic, but does occur almost annually.[46] Tokyo also often sees typhoons each year, though few are strong. The last one to hit was Fitow in 2007,[47][dubious ] while the wettest month since records began in 1876 has been October 2004 with 780 millimetres (30 in)[48] including 270.5 millimetres (10.6 in) on the ninth of that month.[49]

| Climate data for Tokyo (Ōtemachi, Chiyoda ward,[50] 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.8 (73) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.1 (88) |

27.2 (81) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

20.0 (67.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.9 (66) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.1 (70) |

15.4 (59.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

13.0 (55.3) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 52.3 (2.059) |

56.1 (2.209) |

117.5 (4.626) |

124.5 (4.902) |

137.8 (5.425) |

167.7 (6.602) |

153.5 (6.043) |

168.2 (6.622) |

209.9 (8.264) |

197.8 (7.787) |

92.5 (3.642) |

51.0 (2.008) |

1,528.8 (60.189) |

| Snowfall cm (inches) | 5 (2) |

5 (2) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

11 (4.3) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.5 | 5.5 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 101.3 |

| Avg. snowy days | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 9.7 |

| % humidity | 49 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 72 | 73 | 71 | 71 | 66 | 59 | 52 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 187.9 | 167.3 | 163.1 | 175.4 | 172.5 | 123.2 | 143.9 | 175.3 | 117.8 | 133.4 | 146.6 | 175.0 | 1,881.3 |

| Source #1: Japan Meteorological Agency [51] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: World Meteorological Organisation (rainy days)[52] | |||||||||||||

Western areas of mainland Tokyo lie in the humid subtropical climate zone with a dry winter (Köppen classification Cwa).

| Climate data for Tokyo (Ogouchi, Okutama town, 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.9 (75) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.0 (41) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 44.1 (1.736) |

50.0 (1.969) |

92.5 (3.642) |

109.6 (4.315) |

120.3 (4.736) |

155.7 (6.13) |

195.4 (7.693) |

280.6 (11.047) |

271.3 (10.681) |

172.4 (6.787) |

76.7 (3.02) |

39.9 (1.571) |

1,623.5 (63.917) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 147.1 | 127.7 | 132.2 | 161.8 | 154.9 | 109.8 | 127.6 | 148.3 | 99.1 | 94.5 | 122.1 | 145.6 | 1,570.7 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency [53] | |||||||||||||

Tokyo's easternmost territory, the island of Minamitorishima (Marcus Island) in Ogasawara village, is in the Tropical savanna climate zone (Köppen classification Aw). Tokyo's Izu and Ogasawara islands are affected by an average of 5.4 typhoons a year, compared to 3.1 in mainland Kantō.[54]

Environment[edit]

Tokyo has enacted a measure to cut greenhouse gases. Governor Shintaro Ishihara created Japan's first emissions cap system, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emission by a total of 25% by 2020 from the 2000 level.[55] Tokyo is an example of an urban heat island, and the phenomenon is especially serious in its special wards.[47][56] According to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government,[57] the annual mean temperature has increased by about 3 °C (5.4 °F) over the past 100 years. Tokyo has been cited as a "convincing example of the relationship between urban growth and climate."[58]

In 2006, Tokyo enacted the "10 Year Project for Green Tokyo" to be realised by 2016. It set a goal of increasing roadside trees in Tokyo to 1 million (from 480,000), and adding 1,000 ha of green space 88 of which will be a new park named "Umi no Mori" (sea forest) which will be on a reclaimed island in Tokyo Bay which used to be a landfill.[59] From 2007 to 2010 436 ha of the planned 1,000 ha of green space was created and 220,000 trees were planted bringing the total to 700,000. By 2014 road side trees in Tokyo will increase to 950,000 and a further 300 ha of green space will be added.[60]

Demographics[edit]

| Registered foreign born populations[61] | |

| Country of Birth | Population (2011) |

|---|---|

| 164,199 | |

| 105,522 | |

| 29,540 | |

| 17,342 | |

| 8,750 | |

| 7,786 | |

| 7,177 | |

| 6,064 | |

| 5,238 | |

| 4,945 | |

As of October 2007, the official intercensal estimate showed 12.79 million people in Tokyo with 8.653 million living within Tokyo's 23 wards.[2] During the daytime, the population swells by over 2.5 million as workers and students commute from adjacent areas. This effect is even more pronounced in the three central wards of Chiyoda, Chūō, and Minato, whose collective population as of the 2005 National Census was 326,000 at night, but 2.4 million during the day.[2]

The entire prefecture had 12,790,000 residents in October 2007 (8,653,000 in 23 wards), with an increase of over 3 million in the day. Tokyo is at its highest population ever, while that of the 23 wards peak official count was 8,893,094 in the 1965 Census, with the count dipping below 8 million in the 1995 Census.[citation needed] People continue to move back into the core city as land prices have fallen dramatically.[citation needed]

As of 2005, the most common foreign nationalities found in Tokyo are Chinese (123,661), Korean (106,697), Filipino (31,077), American (18,848), British (7,696), Brazilian (5,300) and French (3,000).

The 1889 Census[citation needed] recorded 1,389,600 people in Tokyo City, Japan's largest city at the time.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Economy[edit]

Tokyo has the largest metropolitan economy in the world. According to a study conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers, the Tokyo urban area (35.2 million people) had a total GDP of US$2.91 trillion in 2012 (at purchasing power parity), which topped that list. 51 of the companies listed on the Global 500 are based in Tokyo, almost twice that of the second-placed city (Paris).[62]

Tokyo is a major international finance centre,[63] houses the headquarters of several of the world's largest investment banks and insurance companies, and serves as a hub for Japan's transportation, publishing, and broadcasting industries. During the centralised growth of Japan's economy following World War II, many large firms moved their headquarters from cities such as Osaka (the historical commercial capital) to Tokyo, in an attempt to take advantage of better access to the government. This trend has begun to slow due to ongoing population growth in Tokyo and the high cost of living there.

Tokyo was rated by the Economist Intelligence Unit as the most expensive (highest cost-of-living) city in the world for 14 years in a row ending in 2006.[64] This analysis is for living a corporate executive lifestyle, with items like a detached house and several automobiles.[citation needed]

Tokyo has been described as one of the three "command centres" for the world economy, along with New York City and London.[65] The Tokyo Stock Exchange is Japan's largest stock exchange, and third largest in the world by market capitalization and fourth largest by share turnover. In 1990 at the end of the Japanese asset price bubble, it accounted for more than 60% of the world stock market value.[66] Tokyo had 8,460 ha (20,900 acres) of agricultural land as of 2003,[67] according to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, placing it last among the nation's prefectures. The farmland is concentrated in Western Tokyo. Perishables such as vegetables, fruits, and flowers can be conveniently shipped to the markets in the eastern part of the prefecture. Komatsuna and spinach are the most important vegetables; as of 2000, Tokyo supplied 32.5% of the komatsuna sold at its central produce market.

With 36% of its area covered by forest, Tokyo has extensive growths of cryptomeria and Japanese cypress, especially in the mountainous western communities of Akiruno, Ōme, Okutama, Hachiōji, Hinode, and Hinohara. Decreases in the price of timber, increases in the cost of production, and advancing old age among the forestry population have resulted in a decline in Tokyo's output. In addition, pollen, especially from cryptomeria, is a major allergen for the nearby population centres. Tokyo Bay was once a major source of fish.[citation needed] Currently, most of Tokyo's fish production comes from the outer islands, such as Izu Ōshima and Hachijōjima. Skipjack tuna, nori, and aji are among the ocean products.[citation needed]

Tourism in Tokyo is also a contributor to the economy. In 2006, 4.81 million foreigners and 420 million Japanese visits to Tokyo were made; the economic value of these visits totaled 9.4 trillion yen according to the government of Tokyo. Many tourists visit the various downtowns, stores, and entertainment districts throughout the neighbourhoods of the special wards of Tokyo; particularly school children on class trips, a visit to Tokyo Tower is de rigueur. Cultural offerings include both omnipresent Japanese pop culture and associated districts such as Shibuya and Harajuku, subcultural attractions such as Studio Ghibli anime centre, as well as museums like the Tokyo National Museum, which houses 37% of the country's artwork national treasures (87/233).

Transportation[edit]

Tokyo, as the centre of the Greater Tokyo Area, is Japan's largest domestic and international hub for rail, ground, and air transportation. Public transportation within Tokyo is dominated by an extensive network of clean and efficient[68] trains and subways run by a variety of operators, with buses, monorails and trams playing a secondary feeder role.

Within Ōta, one of the 23 special wards, Haneda Airport offers domestic and international flights. Outside Tokyo, Narita International Airport, in Chiba Prefecture, is the major gateway for international travelers to Japan and Japan's flag carrier Japan Airlines, All Nippon Airways, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines all have a hub at this airport.

Various islands governed by Tokyo have their own airports. Hachijō-jima (Hachijojima Airport), Miyakejima (Miyakejima Airport), and Izu Ōshima (Oshima Airport) have services to Tokyo International and other airports.

Rail is the primary mode of transportation in Tokyo, which has the most extensive urban railway network in the world and an equally extensive network of surface lines. JR East operates Tokyo's largest railway network, including the Yamanote Line loop that circles the centre of downtown Tokyo. Two different organisations operate the subway network: the private Tokyo Metro and the governmental Tokyo Metropolitan Bureau of Transportation. The metropolitan government and private carriers operate bus routes and one tram route. Local, regional, and national services are available, with major terminals at the giant railroad stations, including Tokyo, Shinagawa, and Shinjuku.

Expressways link the capital to other points in the Greater Tokyo area, the Kantō region, and the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku. In order to build them quickly before the 1964 Summer Olympics, most were constructed above existing roads.[69] Other transportation includes taxis operating in the special wards and the cities and towns. Also long-distance ferries serve the islands of Tokyo and carry passengers and cargo to domestic and foreign ports.

Education[edit]

Tokyo has many universities, junior colleges, and vocational schools. Many of Japan's most prestigious universities are in Tokyo, including University of Tokyo, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Waseda University, and Keio University.[70] Some of the biggest national universities in Tokyo are:

- Hitotsubashi University

- National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies

- Ochanomizu University

- Tokyo Gakugei University

- Tokyo Institute of Technology

- Tokyo Medical and Dental University

- Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

- Tokyo University of Foreign Studies

- Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology

- Tokyo University of the Arts

- University of Electro-Communications

- University of Tokyo

There is only one non-national public university: Tokyo Metropolitan University.

There are also a few universities well known for classes conducted in English and for the teaching of the Japanese language. They include:

- Globis University Graduate School of Management

- International Christian University

- Sophia University

- Waseda University

Tokyo is also the headquarters of the United Nations University.

For an extensive list, see List of universities in Tokyo.

Publicly run kindergartens, elementary schools (years 1 through 6), and Primary schools (7 through 9) are operated by local wards or municipal offices. Public Secondary schools in Tokyo are run by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Board of Education and are called "Metropolitan High Schools". Tokyo also has many private schools from kindergarten through high school.

Culture[edit]

Tokyo has many museums. In Ueno Park, there is the Tokyo National Museum, the country's largest museum and specializing in traditional Japanese art; the National Museum of Western Art and Ueno Zoo. Other museums include the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Odaiba; the Edo-Tokyo Museum in Sumida, across the Sumida River from the centre of Tokyo; the Nezu Museum in Aoyama; and the National Diet Library, National Archives, and the National Museum of Modern Art, which are near the Imperial Palace.

Tokyo has many theatres for performing arts. These include national and private theatres for traditional forms of Japanese drama (such as noh and kabuki) as well as modern drama. Symphony orchestras and other musical organisations perform modern and traditional music. Tokyo also hosts modern Japanese and international pop and rock music at venues ranging in size from intimate clubs to internationally known arenas such as the Nippon Budokan.

Many different festivals occur throughout Tokyo. Major events include the Sannō at Hie Shrine, the Sanja at Asakusa Shrine, and the biennial Kanda Festivals. The last features a parade with elaborately decorated floats and thousands of people. Annually on the last Saturday of July, an enormous fireworks display over the Sumida River attracts over a million viewers. Once cherry blossoms bloom in spring, many residents gather in Ueno Park, Inokashira Park, and the Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden for picnics under the blossoms.

Harajuku, a neighbourhood in Shibuya, is known internationally for its youth style, fashion[71] and cosplay.

Cuisine in Tokyo is internationally acclaimed. In November 2007, Michelin released their guide for fine dining in Tokyo, awarding 191 stars in total, or about twice as many as Tokyo's nearest competitor, Paris. Eight establishments were awarded the maximum of three stars (Paris has 10), 25 received two stars, and 117 earned one star. Of the eight top-rated restaurants, three offer traditional Japanese fine dining, two are sushi houses and three serve French cuisine.[72]

Sports[edit]

Tokyo, with a diverse array of sports, is home to two professional baseball clubs, the Yomiuri Giants who play at the Tokyo Dome and Tokyo Yakult Swallows at Meiji-Jingu Stadium. The Japan Sumo Association is also headquartered in Tokyo at the Ryōgoku Kokugikan sumo arena where three official sumo tournaments are held annually (in January, May, and September). Football clubs in Tokyo include F.C. Tokyo and Tokyo Verdy 1969, both of which play at Ajinomoto Stadium in Chōfu.

Tokyo hosted the 1964 Summer Olympics. The National Stadium, also known as the Olympic Stadium is host to a number of international sporting events. With a number of world-class sports venues, Tokyo often hosts national and international sporting events such as tennis tournaments, swim meets, marathons, rugby union and sevens rugby games, American football exhibition games, judo, and karate. Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium, in Sendagaya, Shibuya, is a large sports complex that includes swimming pools, training rooms, and a large indoor arena. According to Around the Rings, the gymnasium has played host to the October 2011 artistic gymnastics world championships, despite the International Gymnastics Federation's initial doubt in Tokyo's ability to host the championships following the March 11 tsunami.[73] Tokyo was selected to host the 2020 Summer Olympics on September 7, 2013.

In popular culture[edit]

As the largest population centre in Japan and the site of the country's largest broadcasters and studios, Tokyo is frequently the setting for many Japanese movies, television shows, animated series (anime), web comics, and comic books (manga). In the kaiju (monster movie) genre, landmarks of Tokyo are routinely destroyed by giant monsters such as Godzilla and Gamera.

Some Hollywood directors have turned to Tokyo as a backdrop for movies set in Tokyo. Well-known postwar examples include Tokyo Joe, My Geisha, Tokyo Story and the James Bond film You Only Live Twice; well-known recent examples include Kill Bill, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, Lost in Translation, Babel, and Inception.

Cityscape[edit]

Architecture in Tokyo has largely been shaped by Tokyo's history. Twice in recent history has the metropolis been left in ruins: first in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake and later after extensive firebombing in World War II.[74] Because of this, Tokyo's urban landscape consists mainly of modern and contemporary architecture, and older buildings are scarce.[74] Tokyo features many internationally famous forms of modern architecture including Tokyo International Forum, Asahi Beer Hall, Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower, NTT Docomo Yoyogi Building and Rainbow Bridge. Tokyo also features two distinctive towers: Tokyo Tower and the new Tokyo Skytree which is the tallest tower in Japan and the second tallest structure in the world.[75]

Tokyo also contains numerous parks and gardens.There are four national parks in Tokyo Prefecture, including the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park, which includes all of the Izu Islands.

International relations[edit]

Tokyo is the founder member of the Asian Network of Major Cities 21 and is a member of the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. Tokyo was also a founding member of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group.

Twin towns and sister cities[edit]

Tokyo is twinned with the following cities and states:[76]

New York, United States (since 1960)[77]

New York, United States (since 1960)[77] Beijing, China (since 1979)

Beijing, China (since 1979) Paris, France (since 1982)

Paris, France (since 1982) New South Wales, Australia (since 1984)

New South Wales, Australia (since 1984) Seoul, South Korea (since 1988)[78][79]

Seoul, South Korea (since 1988)[78][79] Jakarta, Indonesia (since 1989)

Jakarta, Indonesia (since 1989) São Paulo State, Brazil (since 1990)

São Paulo State, Brazil (since 1990) Cairo, Egypt (since 1990)

Cairo, Egypt (since 1990) Moscow, Russia (since 1991)

Moscow, Russia (since 1991) Berlin, Germany (since 1994)[80]

Berlin, Germany (since 1994)[80] Rome, Italy (since 1996)

Rome, Italy (since 1996)

Partnerships[edit]

In addition, Tokyo has a "partnership" agreement with:

London, United Kingdom

London, United Kingdom

See also[edit]

- List of development projects in Tokyo

- Tokyo dialect

- Yamanote and Shitamachi

- World's largest cities

- List of cities proper by population

- List of urban areas by population

- List of cities with the most skyscrapers

- List of urban agglomerations by population (United Nations)

- List of most expensive cities for expatriate employees

- List of metropolitan areas in Asia

- Largest cities in Asia

- Megacity

References[edit]

- ^ "東京都歌・市歌". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Population of Tokyo". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ^ "大都市圏・都市圏の人口". Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved 2005.

- ^ "Geography of Tokyo". Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

- ^ "Japan’s Local Government System". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ "World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision Population Database". United Nations. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Tōkyō" in Japan Encyclopedia, pp. 981-982, p. 981, at Google Books; "Kantō" in p. 479, p. 479, at Google Books

- ^ Fortune. "Global Fortune 500 by countries: Japan". CNN. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2008". Lboro.ac.uk. 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "A.T. Kearney Global Cities Index, 2012". A.T. Kearney. Retrieved 2012-04-02.[dead link]

- ^ The Mercer 2012 Cost of Living Survey

- ^ Fawkes, Piers (2009-06-18). "Top 25 Most Liveable Cities 2009 - Monocle". PSFK.com. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ (Japanese) "「ミシュランガイド東京・横浜・鎌倉2011」を発行 三つ星が14軒、二つ星が54軒、一つ星が198軒に", Michelin Japan, November 24, 2010.

- ^ Tokyo is Michelin's biggest star From The Times November 20, 2007

- ^ Tokyo 2020 - Olympic Summer Games

- ^ a b Room, Adrian. Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company (1996), p360. ISBN 0-7864-1814-1.

- ^ US Department of State. (1906). A digest of international law as in diplomatic discussions, treaties and other international agreements (John Bassett Moore, ed.), Vol. 5, p. 759; excerpt, "The Mikado, on assuming the exercise of power at Yedo, changed the name of the city to Tokio".

- ^ Fiévé, Nicolas and Paul Waley (2003). Japanese Capitals in Historical Perspective: Place, Power and Memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo. p. 253.

- ^ "明治東京異聞~トウケイかトウキョウか~東京の読み方" Tokyo Metropolitan Archives (2004). Retrieved on September 13, 2008. (Japanese)

- ^ Nussbaum, "Provinces and prefectures" at p. 780, p. 780, at Google Books

- ^ McClain, James et al., James (1994). Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era. p. 13.

- ^ Sorensen, Andre (2004). The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty First Century. p. 16.

- ^ "History of Tokyo". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Tokyo-Yokohama earthquake of 1923

- ^ Tipton, Elise K. (2002). Modern Japan: A Social and Political History. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 0-585-45322-5.

- ^ "Tokyo Narita International Airport (NRT) Airport Information (Tokyo, Japan)"

- ^ "Rail Transport in The World's Major Cities" (PDF). Japan Railway and Transport Review. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Saxonhouse, Gary R. (ed.); Robert M. Stern (ed.) (2004). Japan's Lost Decade: Origins, Consequences and Prospects for Recovery. Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-4051-1917-9.

- ^ "Shift of Capital from Tokyo Committee". Japan Productivity Center for Socio-Economic Development. Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-14.[dead link]

- ^ "Policy Speech by Governor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara at the First Regular Session of the Metropolitan Assembly, 2003". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 2007-10-17.[dead link]

- ^ "Despite Major Earthquake Zero Tokyo Buildings Collapsed Thanks to Stringent Building Codes". Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (March 11, 2011). "Japan earthquake disrupts Tokyo, leaves capital only lightly damaged". http://www.latimes.com/. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Tokyo Radiation Levels- Metropolis Magazine". Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Tokyo radiation levels – daily updates – April". Retrieved 11 October 2011.[dead link]

- ^ IOC selects Tokyo as host of 2020 Summer Olympic Games

- ^ "Population of Tokyo, Japan". mongabay. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ "Local Government in Japan" (PDF). Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. p. 8. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ The Structure of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Tokyo government webpage)

- ^ Population of Tokyo - Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Retrieved on July 4, 2009)

- ^ "Development of the Metropolitan Centre, Subcentres and New Base". Bureau of Urban Development, Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ "General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture". Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "A New 1649-1884 Catalog of Destructive Earthquakes near Tokyo and Implications for the Long-term Seismic Process" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ "A new probabilistic seismic hazard assessment for greater Tokyo" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., and McMahon, T. A.: Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1633-1644, 2007.

- ^ "Extreme temperatures around the world". Herrera, Maximiliano. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ^ "Tokyo observes latest ever 1st snowfall". Tokyo. Kyodo News. March 16, 2005. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-18.[dead link]

- ^ a b Barry, Roger Graham & Richard J. Chorley. Atmosphere, Weather and Climate. Routledge (2003), p344. ISBN 0-415-27170-3.

- ^ 気象庁 Japan Meteorological Agency. "観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値)". Data.jma.go.jp. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ 気象庁 Japan Meteorological Agency. "観測史上1~10位の値(10月としての値)". Data.jma.go.jp. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ The JMA Tokyo, Tokyo (東京都 東京) station is at 35°41.4′N 139°45.6′E, JMA: 気象統計情報>過去の気象データ検索>都道府県の選択>地点の選択

- ^ "気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service - Tokyo". World Meteorological Organisation. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "気象庁 / 気象統計情報 / 過去の気象データ検索 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ "気象統計情報 / 天気予報・台風 / 過去の台風資料 / 台風の統計資料 / 台風の平年値". Japan Meteorological Agency.

- ^ "World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD)". Wbcsd.org. Retrieved 2008-10-18. [dead link]

- ^ Toshiaki Ichinose, Kazuhiro Shimodozono, and Keisuke Hanaki. Impact of anthropogenic heat on urban climate in Tokyo. Atmospheric Environment 33 (1999): 3897-3909.

- ^ "Heat Island Control Measures". .kankyo.metro.tokyo.jp. 2007-01-06. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Barry, Roger Graham; Chorley, Richard J.. Atmosphere, Weather and Climate. London: Methuen Publishing. p. 344. ISBN 0-416-07152-X.

- ^ http://www.metro.tokyo.jp/ENGLISH/PLAN/DATA/10yearplan_data_4.pdf

- ^ "2012 Action Program for Tokyo Vision 2020 - Tokyo Metropolitan Government". Metro.tokyo.jp. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- ^ "Tokyo Statistical Yearbook 2011, Population" (PDF). Bureau of General Affairs, Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Global 500 Our annual ranking of the world's largest corporationns". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ "Financial Centres, All shapes and sizes". The Economist. 2007-09-13. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ "Oslo is world's most expensive city: survey". Reuters. January 31, 2006. Retrieved February 1. [dead link] (inactive).

- ^ Sassen, Saskia (2001). The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07063-6.

- ^ "Tokyo stock exchange". Stock-market.in. Retrieved 2010-10-29.[dead link]

- ^ Horticulture Statistics Team, Production Statistics Division, Statistics and Information Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (July 15, 2003). "Statistics on Cultivated Land Area". Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-10-18.[dead link]

- ^ "A Country Study: Japan". The Library of Congress. pp. Chapter 2, Neighbourhoods. Retrieved 2007-10-24.

- ^ "Revamping Tokyo's expressways could give capital a boost". Yomiuri Shimbun. Retrieved 2012-10-08.[dead link]

- ^ "The Times Higher Education - QS World University Rankings 2008". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved 2008-11-11.[dead link]

- ^ Perry, Chris (2007-04-25). Rebels on the Bridge: Subversion, Style, and the New Subculture (Flash). Self-published (Scribd). Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ "Tokyo 'top city for good eating'". BBC NEWS. November 20, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ "Tokyo Keeps Gymnastics Worlds, Bolsters Olympics Ambitions". Aroundtherings.com. 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2012-12-23.[dead link]

- ^ a b Hidenobu Jinnai. Tokyo: A Spatial Anthropology. University of California Press (1995), p1-3. ISBN 0-520-07135-2.

- ^ "Tokyo - GoJapanGo". Tokyo Attractions - Japanese Lifestyle. Mi Marketing Pty Ltd. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Sister Cities (States) of Tokyo - Tokyo Metropolitan Government". Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ^ "NYC's Partner Cities". The City of New York. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

- ^ "International Cooperation: Sister Cities". Seoul Metropolitan Government. www.seoul.go.kr. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Seoul -Sister Cities [via WayBackMachine]". Seoul Metropolitan Government (archived 2012-04-25). Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ^ "Berlin - City Partnerships". Der Regierende Bürgermeister Berlin. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2013-09-17.[dead link]

Bibliography[edit]

- Fiévé, Nicolas and Paul Waley. (2003). Japanese Capitals in Historical Perspective: Place, Power and Memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo. London: RoutledgeCurzon. 10-ISBN 070071409X/13-ISBN 9780700714094; OCLC 51527561

- McClain, James, John M Merriman and Kaoru Ugawa. (1994). Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 10-ISBN 0801429870/13-ISBN 9780801429873; OCLC 30157716

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 10-ISBN 0-674-01753-6; 13-ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Sorensen, Andre. (2002). The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty First Century. London: RoutledgeCurzon. 10-ISBN 0415226511/13-ISBN 9780415226516; OCLC 48517502

Further reading[edit]

Guides[edit]

- Bender, Andrew, and Timothy N. Hornyak. Tokyo (City Travel Guide) (2010) excerpt and text search

- Mansfield, Stephen. Dk Eyewitness Top 10 Travel Guide: Tokyo (2013)excerpt and text search

- Waley, Paul. Tokyo Now and Then: An Explorer's Guide. (1984). 592 pp

- Yanagihara, Wendy. Lonely Planet Tokyo Encounter (2012) excerpt and text search

Contemporary[edit]

- Allinson, Gary D. Suburban Tokyo: A Comparative Study in Politics and Social Change. (1979). 258 pp.

- Bestor, Theodore. Neighbourhood Tokyo (1989). online edition

- Bestor, Theodore. Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Centre of the World, (2004) online edition

- Fowler, Edward. San’ya Blues: Labouring Life in Contemporary Tokyo. ( 1996) ISBN 0801485703.

- Friedman, Mildred, ed. Tokyo, Form and Spirit. (1986). 256 pp.

- Jinnai, Hidenobu. Tokyo: A Spatial Anthropology. (1995). 236 pp.

- Reynolds, Jonathan M. "Japan's Imperial Diet Building: Debate over Construction of a National Identity." Art Journal. 55#3 (1996) pp 38+. 's%20Imperial%20Diet%20Building%3a%20Debate%20over%20Construction%20of%20a%20National%20Identity online edition[dead link]

- Sassen, Saskia. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo.(1991). 397 pp.

- Sorensen, A. Land Readjustment and Metropolitan Growth: An Examination of Suburban Land Development and Urban Sprawl in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (2000) excerpt and text search

- Waley, Paul. "Tokyo-as-world-city: Reassessing the Role of Capital and the State in Urban Restructuring." Urban Studies 2007 44(8): 1465-1490. Issn: 0042-0980 Fulltext: Ebsco

External links[edit]

| Find more about Tokyo at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions and translations from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| News stories from Wikinews | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Travel guide from Wikivoyage | |

.jpg/500px-Skyscrapers_of_Shinjuku_2009_January_(revised).jpg)